Module Three: Institution Watch

“In an institution, you’re taught that no one loves you, or cares for you, you’re a threat to society. You get thrown away and forgotten. You end up dying in the institution. Some already have.”

— Donnie MacLean, Nova Scotia Survivor

Paving The Way Forward in British Columbia M3.V1

In the early days, families had to get creative and be resourceful. They worked hard to turn their vision for their children into a reality. Watch this video to hear about a movement of families in British Columbia.

A Spark of Change

The period of de-institutionalization is an important topic to explore. In Module two, you explored several concepts and ideas. These concepts and beliefs kept people with intellectual disabilities imprisoned in institutions and segregated from society for decades. However, from 1945 to 1982, a series of important shifts took place in Canadian society that inspired a movement of people to act and push governments to close institutions. This movement joined other movements, like the civil rights movement, to draw attention to the human rights of Canadians who have a disability.

The spark that ignited this shift took place when the public began to learn about the serious abuse that was happening in institutions. Survivor experiences were being heard and the truth came out. Stories about life inside an institution were shared across Canada, the United States and Europe. Some journalists visited institutions and secretly filmed life inside. This caused governments to conduct investigations and publish reports. Pierre Burton and Burton Blatt were two reporters who showed the public what was happening to residents on the inside. In 1971, the ‘Williston Report’ was prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Health. This report is an example of an inquiry that was made by the Ontario government. It documents several cases of abuse and some deaths caused by serious neglect. Together, all of these things provoked an outcry for justice. Disability rights advocates began to call for the government to close institutions and families continued to organize themselves to advocate for community-based supports for their loved ones.

To learn more about social movements in Canada that impacted the evolution of disability rights, please visit the student workbook (M3.2).

Patterns of Institutions and Institutional Models |

Survivor’s testimonies tell us what kind of harmful and abusive situations happen in institutions. Putting lots of people together in one place is dangerous. When people have very little control in these places they are not safe. Some examples of institutions that fit this pattern are:

In a CBC interview in 2018, Katherine Rossiter said, “I have yet to find an institution that meets these criteria that isn’t violent.” Rossiter and Dr. Jen Rinaldi from the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE) have done research on violence in institutions.1 They created a check list of six things about institutions. When you can say yes to these five things then bad things are likely to happen to people.2 Institutions breed violence when (they):

These things can also apply to the inappropriate environments where Canadians with disabilities continue to be placed, including nursing homes and long-term care facilities. In the same 2018 CBC interview, Rossiter stated, “What we talk about…are the ways in which institutions are designed to be violent. It isn’t a matter of just some bad staff. It’s a matter of institutional design and that’s why the pattern holds across [all types of] institutions.” She also concluded, “I think, for me, the message is, how do we begin to centre ourselves as a society on the actual care and maintaining the humanity of people who are considered vulnerable, who are outside of everyday society? How do we centre ourselves on their care and move away from institutional models?”3 In the future, Canadians will need to continue to be aware of the danger that people with disabilities are in. As long as large facilities and institutional mindsets exist people are at risk of institutionalization. This is something the next generation will need to overcome. |

The Woodlands Asylum

The demolition of Woodlands was an important event for survivors of this institution. It signified that no one could be harmed in that place again.

This institution was formally known as the Provincial Hospital for the Insane when it was built in 1878. The institution was closed in 1996. The story of Woodlands illustrates the journey of deinstitutionalization in the province of British Columbia.

The following is a case study about the Woodlands Asylum. This institution was formally known as the Provincial Hospital for the Insane when it was built in 1878. The institution was closed in 1996. The story of Woodlands illustrates the journey of deinstitutionalization in the province of British Columbia.

Further links to explore:

Article On the Demolition of Woodlands

NEAL HALL, VANCOUVER SUN 10.19.2011

METRO VANCOUVER — Goodbye and good riddance, said dozens of survivors of Woodlands School as they watched the demolition Tuesday of the 133-year-old centre block tower, the last remnant of an institution known as the Provincial Lunatic Asylum when it was built in 1878.

“Today is a triumphant day for me, it’s a dream come true,” Carol Dauphinais, a Woodlands survivor, told about 150 people who came to watch the New Westminster building being torn down.

“I thought I’d never see the day when this place was knocked down,” she said. “It will put memories in the dirt where they belong.”

Dauphinais said later during an interview that she was put in Woodlands when she was 16 after being in a series of foster homes.

“I died a thousand deaths the first time I lived there,” she recalled. “I had no idea what was going on.” She was told by staff that she was retarded and would never be normal, she added. “They didn’t have to tell me I was retarded — my parents did a good job of that,” Dauphinais said. During a trip out of Woodlands to visit a relative in 1963, she ran away and proved everyone wrong.

“I got a job and worked for 33 years,” she said, proudly adding that she even became a union shop steward during her years working in hospitals.

She said she still would like an apology from the government for the fear and abuse she suffered at the facility, which closed in 1996.

The cellblock tower was the last remaining major building at the site, which housed almost 1,500 mentally disabled children during its peak. Investigations found about 20 per cent of children suffered systemic physical, mental and sexual abuse at the facility.

The asylum name was changed to the Provincial Hospital for the Insane in 1897. In 1950, it became known as the Woodlands School, when it began housing mentally disabled children, as well as runaways, orphans and wards of the state.

The site now is being redeveloped for residential use. Fires destroyed the facility’s other buildings in 2008.

Survivors of the school filed a class-action lawsuit in 2002 and 850 former students were expected to be eligible to receive compensation. The provincial government agreed in 2009 to settle with Woodlands survivors for between $3,000 and $150,000, depending on the level of abuse each person suffered.

The settlement was reached following a report by former B.C. ombudsman Dulcie McCallum that documented systemic abuse at the school.

The courts have excluded survivors who suffered abuse before Aug. 1, 1974, which is when the Crown Proceedings Act took effect, giving citizens the right to sue the B.C. government for wrongdoing.

Advocates have urged the government to ignore the 1974 cutoff date and compensate all those who suffered abuse, but the government has so far refused.

In August, B.C. NDP leader Adrian Dix called on the government to provide compensation for all former Woodlands students who were abused, not just those who were there after 1974.

“Today, survivors of Woodland will witness the demolition of the centre block where so many suffered tragic and horrific abuse,” Dix said Tuesday in a statement.

“While tearing down this site will provide some relief to former students, it will still not close one of the darkest chapters of B.C. history.”

Faith Bodnar, executive director of the B.C. Association for Community Living, told Tuesday’s gathering for the demolition that Woodlands “symbolizes a dark part of our history that we must always remember, continue to learn from and never return to.”

Bill McArthur, a Woodlands resident between 1964 and 1975, said while standing in front of the cellblock tower that he can still remember the fear of living on ward 74 next door.

When he was five or six, he recalled, he was stripped naked and left on an open veranda in winter.

He said he is upset that the government has failed to provide compensation to even the restricted number of survivors qualifying for it.

“This government has totally jacked us around,” McArthur said, complaining that so far, it has only provided Woodlands files to eight people to enable them to support their claims.

“The government sold this land for $18 million but not a dime has gone to the survivors,” he said.

“The only way closure can happen is if all the victims can claim the compensation they deserve,” McArthur said.

The last remaining remnant of the Woodlands Asylum stands as a memorial to the people whose lives were lost in this dark place.

Keeping Provinces Accountable

“Provinces started replacing institutions with smaller facilities. They got rid of the system of the large facilities and replaced them with smaller facilities. Anyone in the know sees that group homes are small institutions.”

— John Cox, Nova Scotia Survivor

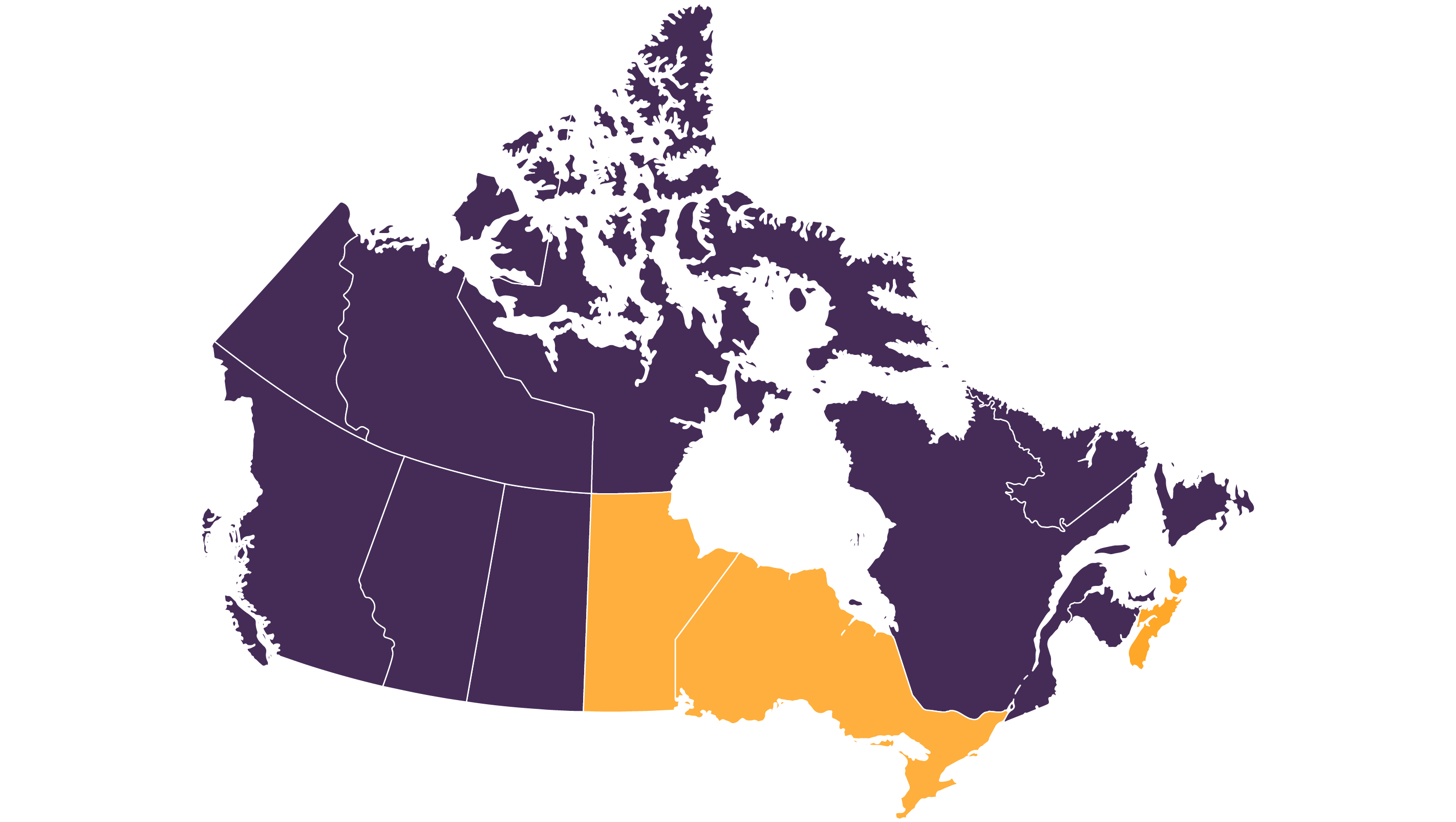

Below, we have created three provincial profiles for you to explore. In each profile, we have collected information about the ways institutionalization impacts people’s lives today. Each of the provinces we have profiled is currently tackling a variety of barriers to full inclusion and are at different stages of deinstitutionalization. The focus of this investigation is for you to discover the state of institutionalization in different parts of Canada, to understand some of the key issues and what still needs to change.

Manitoba

In 2021, the government of Manitoba announced that the Manitoba Developmental Centre (MDC) will be closing. The centre is an institution for people with intellectual disabilities. It has been in operation for more than one hundred years. For more than thirty years, activists have been educating the public and trying to close down MDC and other large institutions in Canada. Over the next three years, over 100 residents will be moving into the community.

Ontario

In 1970, Ontario had 19 large government-funded institutions that kept 7,256 people with disabilities locked away. In 2009, Ontario closed the doors to its last institution. Recently, large apartment complexes, isolated communities, and long-term care homes for children with disabilities have been funded by governments and private developers. In 2020, the Canadian Armed Forces drew attention to examples of abuse and neglect in long-term care in its report during the COVID-19 pandemic. Is history repeating itself in Ontario?

Nova Scotia

On July 15, 2020, CBC News reported that the Breton Ability Centre broke ground on construction of a new “home for children who have autism spectrum disorder or intellectual disabilities” in Sydney River, N.S. Survivors and activists are outraged to read that the Nova Scotia government is supporting the construction of what is essentially a new institution for children (aged 2 to 18). Institutionalization is alive and well in Canada.

Module Three Reflections M3.V5

In this video, Nicole reflects on what has been learned in Module three.

Independent Study

The movement of deinstitutionalization has many victories, as well as many defeats. However, survivors and their stories demonstrate that the road to real inclusion is one where people who have a disability exercise their right to live in the community. The benefits of being a valued member of the community are endless, and so are the possibilities for a good and meaningful life.

We encourage you to take a minute to hear the story of Mr. Gord Ferguson (1948-2018). Mr. Ferguson was a pioneer of disability rights in Canada. His dedication to creating a better life for himself and others, as well as his personal integrity, made him a great friend, husband and teacher.

In the student workbook (M3.6), we have included a short excerpt from Mr. Ferguson’s book, Never Going Back, in which he discusses the closing of the Rideau Regional Centre (RRC), where he spent 16 years of his life. Mr. Ferguson tried to run away from RRC 13 times.

1.

K. Rossiter & J. Rinaldi, Punishing Conditions: Institutional Violence and Disability, 2018.